News Source

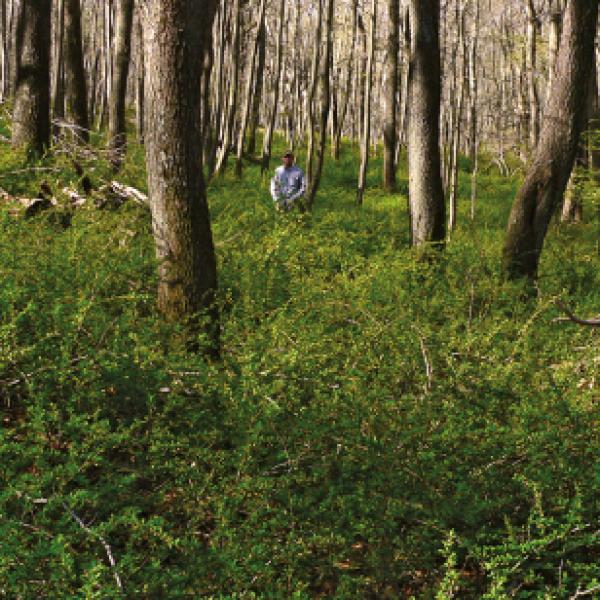

A long-term study of managing Japanese barberry (Berberis thunbergii) shows that clearing the invasive shrub from a wooded area once can lead to a significant reduction in abundance of blacklegged ticks (Ixodes scapularis) for as long as six years.

Published last week in Environmental Entomology, the new research follows up on previous findings of the relationship between Japanese barberry and ticks and details the long-term impact that effective management of the plant can have on the Lyme-disease vector. However, the research team led by Scott C. Williams, Ph.D., at the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, recommend returning to clear Japanese barberry roughly every five years, as their study showed an eventual rebound in barberry and tick abundance in the latter years of their nine-year study.

“The Japanese barberry growth form creates a humid microclimate that favors blacklegged tick survival by increasing questing time, which increases the chances of a successful bloodmeal and ultimately, reproduction,” Williams says. “Managing Japanese barberry significantly reduced humidity levels to equal that of areas without barberry, and we saw a significant decline in tick abundances up until about year 5 post-barberry treatment.”

The study tracked levels of Japanese barberry and blacklegged ticks in six locations in Connecticut. At each, three separate plots were monitored: one with barberry left intact; one with barberry cleared with a combination of mechanical removal, herbicide treatment, and flame treatment; and one where no barberry was present at all. They found that clearing the barberry reduced tick abundance—and abundance of ticks infected with the bacterium that causes Lyme disease—in the managed plots nearly equal to the levels of the no-barberry plots. The reduction occurred beginning in the third year post-clearing, and those levels remained low through year five. (The tick’s two-year life cycle accounts for the delay, as year two is the first year that juvenile ticks are exposed to the harsher, less-humid conditions in the cleared plots, leading to a reduction in adult abundance in year three.)

After about five years, barberry and tick abundance began to creep back upward; the researchers did not monitor relative humidity (RH) in the plots beyond year five, but they write that they “would speculate that areas where barberry was managed would become increasingly less hostile to I. scapularis survival over time as periods of higher RH would recover as barberry and other invasives recovered.”

Williams’ research has turned to other aspects of tick ecology, but he hopes others will further his colleagues’ work by examining management of other plants, such as ferns, burning bush, or huckleberry, all of which could perhaps provide the same microclimate friendly to ticks.

“My legs are permanently scarred from the barberry thorns, and I have had Lyme disease three times as a result of the research, but it has been worth it to educate the public how a non-native invasive shrub can alter native ecosystems and can have indirect negative effects on public health,” he says.