News Source

This winter has been the warmest on record in much of New England. And while many people enjoyed the T-shirt weather, it made Claire E. Rutledge, a researcher with Connecticut’s Agricultural Experiment Station, more concerned about what next season may hold.

Beginning in April, she will head to Wharton Brook and other state lands, setting traps for the southern pine beetle and checking them weekly through midsummer.

The beetles, which can kill thousands of trees in epidemic attacks, had never been found beyond the pitch pine forests of the American South, because the winters were too cold. But they have migrated to New Jersey, where they have destroyed more than 30,000 acres of forest since 2002. And the warmer winters have now beckoned them to New England.

Alarmed scientists first discovered the beetles last year along a front stretching more than 200 miles, from central Long Island to Cape Cod and Martha’s Vineyard, a region long thought to be far too frigid for these tiny beetles, barely different in size and color from a chocolate sprinkle.

“When I heard they caught a live beetle in Massachusetts,” Dr. Rutledge said, “that really freaked me out.”

Now that the beetles are in New England, they are probably there to stay, state and environmental officials said. And if there is a severe outbreak, the region could lose much of its pitch pine forests. Many of the forests are already unhealthy, a result of overcrowding, making them especially susceptible to the pine beetle’s attacks — boring through bark, laying eggs and spreading a crippling fungus — and many state forestry divisions do not have the resources to combat them.

Scientists are concerned that the beetles could destroy the remaining tracts of the pitch pine forest, an ecosystem that once carpeted the Eastern Seaboard but now exists mostly in pockets — the Cape Cod National Seashore, the Albany Pine Bush Preserve and smaller forests — and is home to more than a dozen endangered species, such as the tiger beetle and several types of butterflies.

“I don’t think people have a strong understanding of how at risk these forests are,” said Kevin J. Dodds, a scientist who runs the southern pine beetle response in the Northeast for the United States Forest Service.

An invasion in New England could mean a repeat of what happened in New Jersey and on Long Island, where state agencies were caught off guard, officials say.

“We’re still scratching our heads and asking why we didn’t find this sooner” on Long Island, said Robert Davies, New York’s state forester. By the time they had discovered the infestation, he said, it had ballooned to 10,000 acres. (They have since contained it to about 8,000 acres.)

State environmental officials and federal foresters warned Connecticut that the plague could be headed their way toward the end of 2014, and soon after, they found infested trees in about 20 places across the state. So last spring in much of New England and New York, foresters and state officials set traps to determine if there were more beetles. And there they were, in traps in Bear Mountain State Park in New York; southern Connecticut; Rhode Island; central Massachusetts; and in Cape Cod, Plymouth and Martha’s Vineyard, Mass.

Some scientists see the beetles’ march north as another sign that climate change is disrupting the environment, and not just in ways that damage ecosystems. Heat-loving creatures like ticks and mosquitoes are expanding their ranges, too, carrying illnesses like Lyme disease to Canada and dengue fever to parts of the United States.

And the environmental costs are steep, too. For all the damage wrought by the southern pine beetle, the mountain pine beetle has exacted a far greater toll, ravaging pine forests across the western United States and Canada, destroying tens of millions of acres in places and altitudes once thought beyond their reach.

According to Matthew P. Ayres, a Dartmouth College biologist who studies the southern pine beetle, the warming of winter’s coldest night is the primary cause of their spread. Most beetles die if temperatures fall to around minus 8 degrees Fahrenheit. And while this winter had an unusually cold snap, the low temperatures did not last long enough to wipe out the beetles, Dr. Rutledge said.

Mr. Davies said, “We were still hearing about beetles flying on Christmas Day, and that’s not a good thing.”

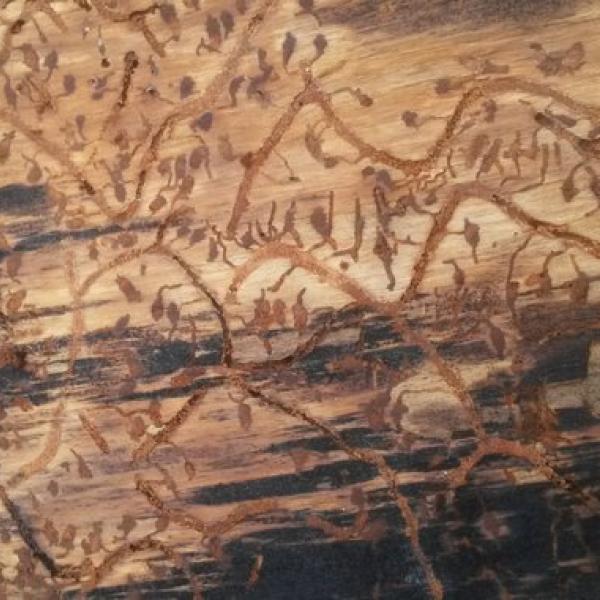

Dr. Dodds and others say that many longstanding practices unintentionally damaged the forests. They were largely left to themselves, resulting in overcrowded stands, where trees had to compete for sunlight and nutrients. In crowded forests, beetle attacks can spread more easily, and the insects overwhelm a tree’s defenses by laying eggs that, once they’ve hatched, hijack the tree’s circulatory system. They also carry a fungus that clogs the tree’s waterways.

With this one-two punch, beetles can wipe out thousands of trees in a season, Dr. Rutledge said. Natural fires, for all the damage they cause, do thin forests and lead to regrowth, but states have worked quickly to extinguish them.

Trees have some defense mechanisms — they release resin, which hardens into little yellow clusters on the bark (commonly referred to as “popcorn”) to fill the holes made by beetles and kill them — but they do not always work.

The pine beetle is no longer considered a big threat in the South because the forests are healthy, a result of decades of thinning efforts, Dr. Ayres said, aided by the region’s large lumber market, where salvaged pines can be sold to mills.

By contrast, there is not always a market for the trees in much of the Northeast.

This spring, scientists and state officials will set more traps in New England and New York. Depending on what they find, they may conduct aerial surveys to see if any trees are in distress. When the trees are in trouble, their needles turn from green to yellow and red, an effect that can be seen best from above.

Dr. Ayres said that if precautions were not taken, a widespread invasion could leave only a few pitch pines in the region.

He also said he could foresee the beetles possibly reaching the Great Lakes states and Canadian provinces, which are heavily forested with red and jack pines and could be vulnerable. From there, they could infiltrate much of Canada, spreading west to meet the mountain pine beetles that have been moving east into Alberta and Saskatchewan, leaving a ring of dead forests around the continent.

“It’s an example of something that’s happening all over the world,” Dr. Ayres said. “It’s old pests in new places, and with that comes a whole new set of challenges.”