Author: Madison Schumacher, VT Aquatic Invasive Species Program Technician, Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation

October 2022

If you spend a lot of time out on freshwater lakes, ponds, and wetlands in the Northeastern United States, you may have noticed large jelly-like masses submerged under water. These slippery, slimy masses were most likely a community of microorganisms called a bryozoan, or Pectinatella magnifica. Often overlooked or mistaken for algae or eggs, there are over 24 freshwater species of bryozoans found in North America with over 5,000 marine bryozoans documented to date (Massard and Geimer 2008). These jelly-like masses are communities formed by tiny filter feeding organisms, called zooids, and often attach to plants, fallen trees, docks, boats and other aquatic substrates.

Bryozoans are found in warm, slow-moving bodies of water in the Northeast and can be identified by their round shape, jelly texture and their brownish green color. The black speckles on the outer layer of the mass are each individual zooid organism (Figure 1). Bryozoans are often referred to as freshwater coral because of the community building behavior of the zooids that make up these colonies. However, bryozoans are not closely related to marine corals. These gelatinous masses feed and reproduce together and range in size depending on the stage of the developing bryophyte. Figure 1 shows a newly forming bryozoan on a branch, however, a single colony can grow up to the size of a basketball.

Zooids live and grow together in the bryozoan form from summer to fall. Zooids use their

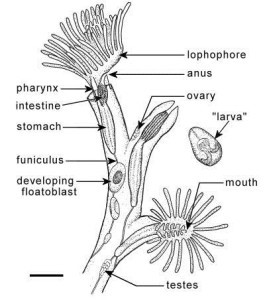

Reproductive system of two zooid individuals in a bryozoan community. Drawing by Dr. Timothy S. Wood (Department of Biological Sciences, Wright University).

tentacle-like limbs called lophophores, to capture algae, diatoms and other organic materials for sustenance (Smith 2001). They can move and swim around freely using these lophophores. They secrete the gelatinous material that provides a protective shell structure and allows the zooids to grow and store seeds in order to grow their colony. Zooids can multiply by sexual and asexual reproduction. At the end of the summer, they release statoblasts or cells encased by a hard outer structure formed inside of the jelly-like mass (Smith 2001). These statoblasts may float around in currents and disperse or, oftentimes, hitch a ride from waterfowl or other aquatic species and remain dormant until the following spring. Zooids can also reproduce asexually by dividing and forming a second colony that is genetically the same. In addition, zooids can sexually reproduce using ovaries and testes ( figure at right).

The native range of freshwater bryozoans in the United States is east of the Mississippi River up to Ontario, Canada (Massard and Geimer 2008). Due to bryozoans’ nature of attaching to substrates, they are often distributed by watercraft, thus their populations are spreading even farther north into Canada. Unfortunately, some species of bryozoans are considered invasive and were initially introduced in waterbodies in Europe in the 1930’s. Today, invasive bryozoans are still of concern to Europe and continue to be spread around the European region (Wyse Jackson and Spencer Jones 2008). There have been sightings of invasive bryozoan colonies that grow to be four feet wide, clogging irrigation or drainage pipes and impeding on recreational water activities.

In addition to anthropogenic effects of bryozoans, studies show that bryozoans can carry parasites to new areas that may cause disease in salmon and other closely related fish species (Wyse Jackson and Spencer Jones 2008). For the most part in the Northeastern United States, bryozoans are completely harmless to humans. Bryozoans are often a sign of a healthy ecosystem. The filter feeding process of bryozoans can keep harmful algal blooms at bay and even increase water clarity.

It is very exciting to encounter a colony of zooids! If you do choose to handle one, be sure to take special care because bryozoans are fragile communities that can easily break apart in your hands. It is important to remember that removing them from their substrate or holding them out of water for longer than a few minutes may be potentially harmful to the colony. Be respectful because those tiny zooids are working hard to keep our water clean!

References

Massard, J. and G, Geimer, G. 2008. Global diversity of bryozoans (Bryozoa or Ectoprocta) in freshwater. Hydrobiologia 595: 93-99.

Smith, D. 2001. Freshwater Invertebrates of the United States. John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, New Jersey, USA.

Wyse Jackson, P. N. and M. E. Spencer Jones. 2008. Annals of Bryozoology 2: aspects of the history of research on bryozoans. International Bryozoology Association, Dublin, viii-442.